Female Study: Sophie Calle's Surveillance

La Coupole, 2018

I’ve been seeing a lot of references to Hitchcock’s Rear Window as we have been in quarantine. I even revisited the film myself at the start of all this, maybe subconsciously picking up what others have… It seems like many of us are watching the world from our windows, and even more so, from our screens. I was about to say that through social media, now more than ever, we have all become voyeurs, watching others’ mundane tasks as if they were of utmost importance. But I looked up the definition of voyeur to write this article, (looking for synonyms), and was surprised to learn that the meaning includes a sexual pleasure in seeing others–usually naked. A lot of us use the word voyeur in everyday language as simply enjoying watching others; I never understood that the word denotes a kind of sexual pleasure in doing so, but I guess I’ve been using it incorrectly.

In artist Sophie Calle’s work, she is frequently called voyeuristic as well, though I’ve never heard her say she derived sexual pleasure from watching others. In fact, her watching others seems more like a way of maintaining isolation, a detachment from others that doesn’t necessarily bring any pleasure. But perhaps I’m reading into her work incorrectly as well, because I found a bio in Electronic Arts Intermix’s website that states:

Calle's works often focus on the nature of desire, and on the relationships between the artist/observer and the objects of her investigations…

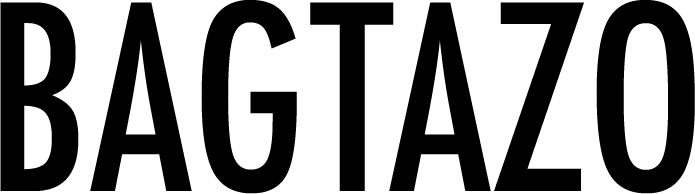

I’ve only recently become aware of Sophie Calle’s work, first discovering her series, The Chromatic Diet, 1998. These photos employ an arbitrary set of constraints, a concept Calle played with again and again, this time creating a daily meal dictated entirely by a specific color. This work is almost a terminus of her conceptual work, in that all the roads she previously took basically led her here.

The work itself was an offshoot of a larger project between Sophie Calle and her friend, writer and film director, Paul Auster. Calle propositioned Auster to write a fictive character in a novel, which Calle would later play out. in response, Auster somewhat reluctantly created character Maria Turner in his 1992 novel Leviathan. The character is a bit of a feedback loop, as Maria Turner is based on Sophie Calle. In the novel Maria Turner, inspired by the arbitrary confines Calle often works within, eats monochromatic meals each day. Maria Turner also dresses herself according to a letter of the alphabet each day, among other restrictions somewhat mocking calle.

In response, as a means to play out Maria Turner’s character, Calle published a book called Double Game in 1999.

Double Game is composed of three parts: Part one plays out Maria Turner’s life, including the Chromatic Diet (it’s unclear if Calle actually ate the meals, but she did make and photograph them). the images from the Chromatic Diet series matchED the exact descriptions of the meals eaten by Maria Turner in Leviathan. Calle also follows Maria’s odd rules of dressing according to the letters of the alphabet; with calle dressed as Bridget Bardot on the letter B’s day on the cover of the book, and others within section one.

The second section takes the story further, again almost as a feedback loop of Calle's earlier works, with a series based on Calle’s earlier works of “seminal narrative” with text and images that were appropriated by Maria in Leviathan.

The third and final section is titled, Gotham Handbook, which was written by Paul Auster. Within the handbook Auster writes instructions for Sophie Calle on how to improve life in New York City through a series of “artistic interventions.” Though Calle was based in Paris, Maria Turner was a photographer based in New York, so this again plays with the feedback loop between Calle and Auster’s fictional character.

I found a great, brief description of the artistic interventions on a blog called Open File, written in 2011:

The instructions given are for Calle to smile at and talk to strangers, distribute sandwiches and cigarettes to the homeless and to “cultivate a spot.”

…what Auster was interested in was pushing Calle from the position of passive observer, which she had occupied throughout her earlier work, into the role of active participant engaging with the city and its inhabitants in a new way. For the spot, Calle chose a phone booth… painting it green and providing a chair, fresh flowers, cigarettes, food and drink.

Auster instructed her to record people’s reactions to the cultivated spot. Leaving pens and paper in the phone booth resulted in a range of comments, both positive and negative, for example: ‘This is bullshit and fucked up. Please take this motherfucker down’, annotated by another commentator, indicating with an arrow: ‘Ignorance surrounds us all'.

Gotham Handbook ends when the telephone company takes down Calle’s intervention and tosses it a nearby bin.

The phone booth Calle commandeered to record people’s reactions to “a cultivated spot” as instructed by Auster in Gotham Handbook. New York City, 2000

Sophie Calle began taking photographs of people in the 1980s. She thought of it almost as a game, where she would give herself rules or challenges to work within. In a short video interview, she describes returning to Paris after a long trip with no job, heartbroken, and somewhat lonely. During this time, she realized there was a paradox of freedom found within rules, so she took this concept and starting taking photographs around Paris.

Her first works were made by following people around the city. Calle described her initial allure to the work as a means of reacquainting herself with Paris after having been gone so long. With this surveillance project, she would fixate on particular individuals, casing them, photographing and taking notes of her observations of the mundane moves they made in public spaces. She would sometimes even follow the individuals home, but never peer into their windows with her camera, instead focusing on the actions they made in public. Nevertheless, if she weren’t an artist, a female, and white, she may have been accused of being a stalker; but with her advantages, she carried out series of works in following others.

Explaining her work, Calle said that in looking for something in another person, she was maybe looking for something in herself. Plus the end use of the findings were to be used as art, so it was not ‘stalking.’ Calle also described a sense of control she felt from this detached work, where she could chose to trail someone for any amount of time, and at her will, she could just as easily terminate the ‘relationship.’

As if in retribution for the inquiries she subjected others to, in 1981, Calle requested that her mother hire a detective to follow Sophie. Just like Calle had, the detective collected photographs and notes on her.

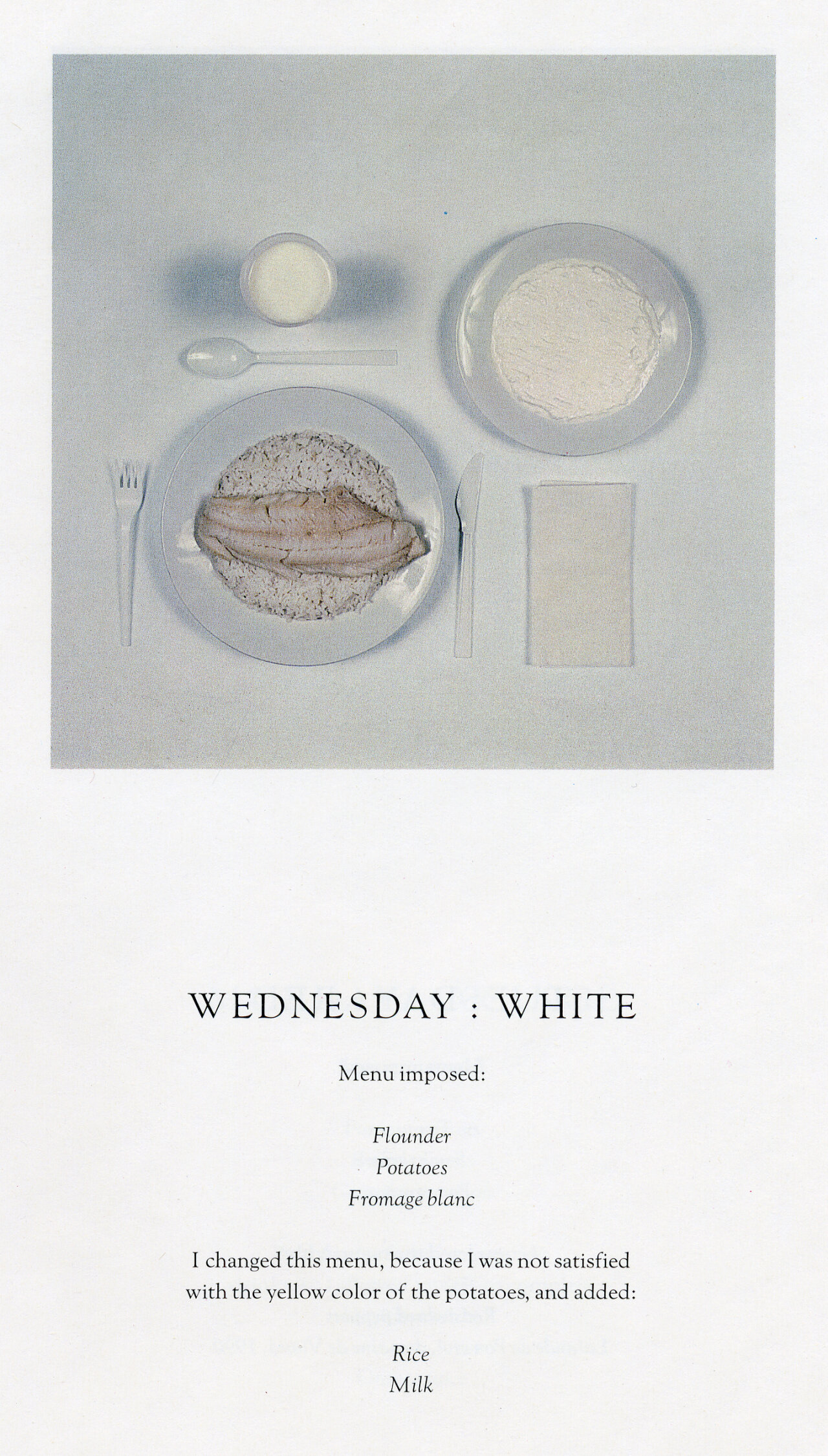

each of Sophie Calle’s projects throughout her life built upon one another, almost like “chapter[s] in a vast overall volume of references and echoes, in which Calle often blurs the boundaries between the intimate and the public, reality and fiction, art and life.” So using her first project in Paris between 1980 - 1981 as a foundation for the years of work to follow, Calle’s following project later published in a book called Suite Vénitienne. is a linear transition from her Paris project, which also creates a stepping stone for the project she began immediately afterwards.

Calle in Suite Vénitienne:

For months I followed strangers on the street. For the pleasure of following them, not because they particularly interested me. I photographed them without their knowledge, took note of their movements, then finally lost sight of them and forgot them.

At the end of January 1980, on the streets of Paris, I followed a man whom I lost sight of a few minutes later in the crowd. That very evening, quite by chance, he was introduced to me at an opening. During the course of our conversation, he told me he was planning an imminent trip to Venice. I decided to follow him.

Some of Calle’s surveillance of the man she followed from Paris to Venice published in Suite Vénitienne

Upon her arrival in Venice, under the guise of working at a chambermaid in a hotel in 1981, Calle continued her conceptual art. During her work at the hotel, she photographed the rooms as others left them. She never peered into their bags, or rifled through their things, but instead took photos of what was left out in the open. In one room she did find that a man left his journal open everyday, and within the pages he documented every thing he ate in detail. Calle photographed each entry as she found them open on their respective days for the duration of the hotel patron’s stay.

Once she completed her work, she compiled the photographs according to their room numbers, including her signature text along side the images for an exhibition simply called l'hôtel. Calle described her interest in a hotel room in particular because the room itself embodies each inhabitant in some way, yet it also stays fixed as its own entity.

Again, it’s amazing That she got away with peering into the private lives of others in such an invasive way, and I do wonder what would have happened to her if she had been caught. Imagine trying to explain conceptual art to the hotel manager!

Following her work in Venice, Calle returned to Paris, where she found an address book of Parisian filmmaker, Pierre D on the ground. Once more building upon her previous works in surveillance as art, before returning the address book to its owner, Calle photocopied its contents in order to conduct a series of interviews with those she found inside the book, building a profile of sorts on Pierre D.

This work was titled l’Homme au carnet, and was published in Parisian newspaper, Libération in 1983. As a result, Calle was persecuted for her inquiry into the private lives of others for the first time, with Peirre D threatening to sue Libération, and demanding that they run nude photos of Calle in their paper in return for publishing her invasive work on him. Eventually, the lawsuit never came to be, and Calle agreed not to publish anything else from l’Homme au carnet until after Pierre D died. (The work can now be found as of 2012 in a book published by Siglio Press, the same publisher of Suite Vénitienne).

Calle continued to build upon her previous works, fascinated by the interface between public and private life, investigating patterns of behavior using techniques similar to that of a private investigator, a psychologist, or a forensic scientist.

As you can see, I called her work with Auster almost a terminus from her previous work, since the culmination of her surveillance, voyeurism, inquiry into the self in public, and what it means to present yourself to others, it’s almost as if the roads she took previously inevitably led her to Double Game.

Spanning from the 1980s, Calle’s work is so vast, I’ve decided to narrow it down to just a few early works and their relationship to Double Game in this article since my entire inquiry began surrounding the Chromatic Diet. But if you’re interested, Calle has made a number of films and other books you can check out.

Last thing I will cover though, is Calle’s Birthday Ceremony, a series of sculptural installations that she compiled over 13 years (roughly 1980 - 1993). The sculptures are physical representations of rituals Calle did in private and shared with others surrounding her birthday. Acting within the made up confines of her own dictated rules, Calle invited people to a birthday dinner every year, the number of guests corresponding to her age. The ritual was created as a way for Calle to cope with insecurity she felt, so each year she took all of the gifts she received from her birthday dinner and put them on display in a glass case. The following year, the gifts would be replaced by the new ones she received. Calle never actually used the gifts after putting them on display, instead packing them away by year into boxes. Finally at her 40th birthday, she proclaimed she was no longer in need of this ritual, as she had cured herself of the kind of insecurity she felt that was remedied by reminders that she had friends.

In 1995, Sophie first documented the objects with photographs, but then created individual displays for all 13 years, which went on display at the Tate Modern in 1998.

Overall, I’m extremely impressed with Calle’s ability to turn what appears to be various neuroses into conceptual art. I believe that many people who create things convert otherwise negative emotions into artworks, but there are few so socially deviant who directly work with the literal experiences of their emotions as Calle.

In a video interview, Calle describes a gallery picking up her work fairly easily, so I can’t help but to imagine that after a long trip with no job, being able to afford to case people, taking film photographs, and hiring a detective, that Calle had family money supporting her when she began her art career in 1980. She likewise seems to have had a network in the art world in Paris. (She also took a trip to Japan to do similar work later, so the lack of financial constraints appears to be a theme). This privilege doesn’t take away from how cool her ideas are, I just feel the need acknowledge privilege when it seems to be present. However, please note this in my own inference based on my research, the assumption has not been verified.

It is very rare that I cover a living artist, partly because I feel like without conducting a proper interview, an article like this is rather invasive, but I think in Sophie Calle’s case, she would be ok with it and not find it creepy. (LOL). Last thing I’ll mention is that the intro image, La Coupole, 2018 is a piece from her series Parce Que a recent body of work where she explores ‘reasons why.’ The work is very personal, almost exhibitionistic, each photograph having an embroidered flap with text explaining “why.” I like how after a while, Calle turns the lens more on herself than on others starting with Birthday ceremony and continued in her work today, but all the while She maintains the very linear thought process that she started with.

Super cool.

Bibliography

Sohpie Calle Biography. Electronic Arts Intermix, year unpublished

Sophie Calle & Paul Auster - Gotham Handbook. Open File, 2011

Sophie Calle Double Game Exhibition. Camden Arts Centre, 1999

Sophie Calle: Double Game (Book Description). New Museum Store, 2007

Sophie Calle: Talking to Strangers. Nicola Homer, Studio International, 2009

Sophie Calle (Biography). Iwona Blawick, Perrotin Gallery, 2019

The Colorful Influence of Sophie Calle’s Chromatic Diet on Modern Food Photography. Phoode

Video: Sohpie Calle’s Voyeuristic Portraits of Hotel Rooms. SFMOMA

The Fertile Mind of Sophie Calle. Mary Kaye Schilling, New York Times, 2017

Art Now: Sophie Calle, The Birthday Ceremony. Frances Morris, Tate Modern

Courtney Bagtazo, Bagtazo © 2020