PERFORMANCE STUDY: YVES KLEIN'S BROKEN BOUNDARIES WITH ANTHROPOMETRY

YVES KLEIN, UNTITLED ANTHROPOMETRY (ANT, 106), 1960

If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard from me since spring, it’s because a lot has been going on with Bagtazo. But today I’m finally back to tell you about Yves Klein.

While scrolling through my Instagram feed recently, I came across a post in which someone had basically recreated Yves Klein’s Anthropometry paintings, albeit in the form of a cell phone video performance. A young woman, naked save for a trench coat and boots, held a bucket of blue paint near a cinderblock wall painted solid white. The footage goes on to show the woman dipping a large paint brush into a bucket of paint, covering the front of her body with it, and then pressing herself against the white wall. The post was published without so much as a nod to Klein, leading users—the majority of which I assume to have been unaware of the content’s historical link to Klein—to comment by the dozens with things like, “COOL,” “YOU NEVER FAIL TO AMAZE ME,” “OMG, I LOVE YOUR WORK,” “Blue heart emoji…”

I of course, was outraged, and commented, “So very Yves Klein #citeyoursources” and proceeded to put my phone away and begin researching Klein for the periodical. (LOL)

Suaire de Mondo Cane, 1961

One of the coolest details of Yves Klein’s work is that he created his own shade of blue, an ultramarine pigment known as International Klein Blue, which he patented in 1961.

(Maybe I’m partial to this detail because I have been gradually working on a piece about pigment, though due to the research being so intense, I have yet to finish. If you’re interested in reading a wonderful article on the history of color, check out this piece from the September 2018 issue of the New Yorker).

To me, color is the foundation of visual arts and is inextricably connected to historical eras. Sepia photographs belong to a specific period, as do the chalky primary colors of the surrealists and suprematists; the bold colors of Bauhaus, the muted, chemical shades of early Kodachrome prints, the neons of the 1980s, millennial pink, and so on…

And so naturally, when I saw Anthropometry being put on via the wrong shade of blue, not to mention sans citation, I cringed. I’m not always such a purist, however given that in the video there were two parts completely poached from Klein’s Anthropometry: color, and the use of the female body as a “living brush,” I just couldn’t let this one go. It’s so frustrating that in this so-called information generation, citation and accuracy are no longer relevant. *Shudder*

Yves Klein was born in Niece, France in 1928. He lived briefly in Japan, where he studied judo, though upon returning to Paris, decided to focus solely on painting. And while his output is impressive in both quality and quantity, Klein himself only lived to the age of 34.

Working in a style that would later be dubbed Nouveau Réalisme, Klein was a pioneer, blurring the lines between conceptual art, sculpture, painting, and performance. His groundbreaking work paved the way for Minimalism and, in the years following his death, Pop Art. Though short-lived, Klein’s contribution to the art world paved the way for New York’s Happenings, performance art, Land and Body Art, and even some aspects of Conceptual Art throughout the 1950’s, when conformity, tradition, and repression were all but the standard of everyday life.

A good amount of Klein’s works are comprised of monochrome paintings, which focused on “the void.” of these works, his signature blue paintings became most well-known. Klein CITES THAT THE ORIGINS OF HIS COMBINING “THE void” and the color blue CAME from literary critic and philosopher Gaston Bachelard who wrote: “First there is nothing, then there is a deep nothing, then there is a blue depth.”

Fixated on finding the perfect blue hue, Klein developed his signature ultramarine with a chemical company to create a polymer binder that could fix the pigment to maintain its color intensity over time. (Many manufacturers and artists struggled with the limitations of pigment technology in the past, as a main issue with certain colors was fading over time).

After success in creating the polymer, which Klein called International Klein Blue (or IKB), he began utilizing the color to begin creating objects of various forms: textured painted canvases, sculptures of sea sponges soaked in the pigment, and field-like floor coverings composed entirely of the powdery blue substance.

Through his work, Klein’s interest in “the void” lead to an attraction to the “immaterial,” which he cites as the reason he began making solid colored paintings with curved edges, which were meant to meld into the background and his blue fields.

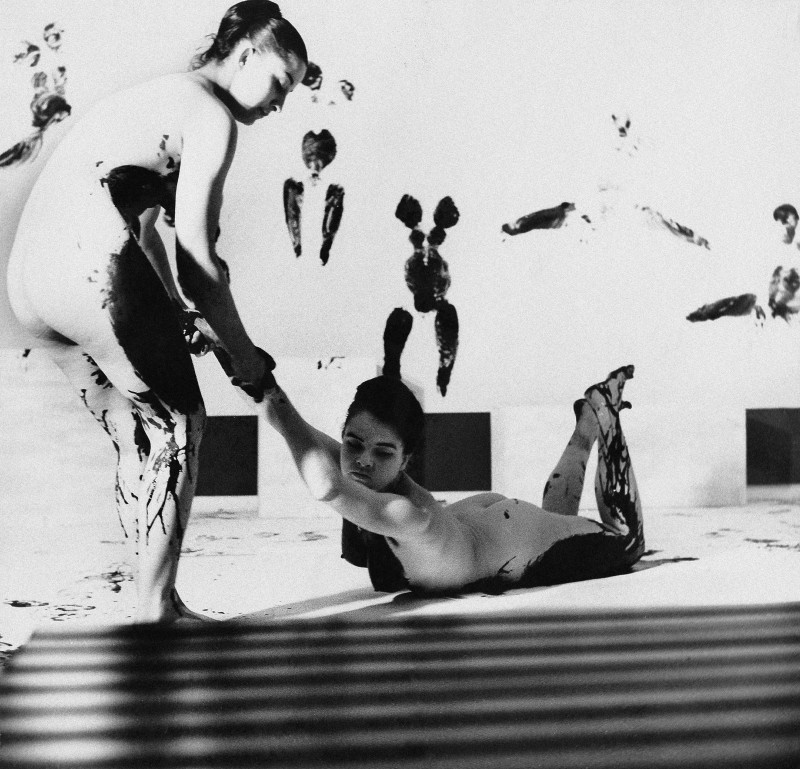

During his blue phase, Klein gained recognition from his work via his “living brushes,” creating artwork he called Anthropometry. After clearing out his studio (another focus on the void), Klein utilized models traditionally employed for figure painting as actual “brushes” for his works with IKB pigment. The body impressions were an adaptation of the marks bodies leave on dojo mats that he witnessed during his martial arts practice in Japan. Klein was interested in distancing himself from the artwork, so using another’s body as a medium between himself and traditional art media became the cornerstone of his conceptual artwork. Soon after he created studio works of this nature, Klein took to having the models paint themselves (under his direction) as performance as well.

I found an explanation for his concept in an excerpt from Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961:

Whatever directed me towards anthropometry?

The answer can be found in my work during the years 1956 to 1957, when I was taking part in the adventure of creating the pictorial immaterial sensitivity. I had just removed from my studio all my former works. The result – an empty studio. My only physical action was to remain in my empty studio, and the creation of my pictorial immaterial states proceeded marvelously. However, little by little, I became mistrustful of myself: but never of the immaterial. I therefore hired models, as other painters do. But unlike the others, I merely wanted to work in their company rather than have them pose for me. I had been spending too much time alone in the empty studio; I no longer wanted to remain alone with the marvelous blue void that was budding. (...)Today, the academicized easel-painters have reached the point of shutting themselves in their studios, confronting the terrifying mirrors of their canvases. Now the reason for my use of nude models becomes quite evident: it was a way of preventing the danger of secluding myself in the overly spiritual spheres of creation, thus rupturing with the most basic common sense, repeatedly affirmed by our incarnate condition. The shape of the body, its lines, its strange colors hovering between life and death, hold no interest for me. Only the essential, pure affective climate of the flesh is valid.

Here is a quick video of Klein’s first performance, Monotone-Silence Symphony in 1960, “a performance in which an orchestra plays a single note for 20 minutes, followed by a 20-minute period of silence, to a large audience. Remarkably, despite the resonance with John Cage’s 4’33” (1952), there is little evidence to show the two artists were aware of each other.” (Artsy).

Some feminists later criticized Klein’s Anthropometry works, claiming that by instructing nude female models, Klein maintained control over his subjects, a factor which would in-turn degrade the female body to the state of a mere object intended solely for the male gaze, flexing and further strengthening patriarchal values. I’m not sure I’m that kind of a feminist, because I agree with art critic and close friend, Pierre Restany, who praised Yves Klein’s artistic philosophy and process that denounced “traditional, conservative, classic French art” OF THE TIME. Since it is difficult to separate the female body from the male gaze, as men perpetually utilize the body as a subject, in hindsight, I can understand this feminist read of the work. But I do not think the use of the body form necessitates the objectification of the female form. Plus at the time, I doubt women would be allowed to do this type of body art and be taken seriously, and I feel the work itself extremely important.

As writer Tess Thackara states, “The performances can arguably be read not as action paintings in which women become passive instruments, but as performances in which creator (in this case Klein’s female performers), artwork, and audience become one.”

Anyway, Yves Klein did a lot more than Anthropometry, and has amazing website that’s maintained by his estate where you can see his works.

I admit I didn’t look too depply into the cause of Klein’s premature death, though I did learn he died of a heart attack at age 34. I’m currently 34, and so when I read this, I wondered whether I’d be satisfied with my body of work were I to die right now, and I have to say, I’m glad I have more time because I have so much more I want to do. That said, I’m thoroughly impressed with how much Klein was able to do in 8 years and am hopeful that in another 4 (Bagtazo was established in 2014), maybe I could die happily…

Not sure if it’s a myth (a lot of what I’ve read about Yves Klein seems like hyperbole (possibly self-made), but if it’s true, Klein’s focus on the void and immaterialism was even embraced before his death where he’s quoted as saying, "I am going to go into the biggest studio in the world, and I will only do immaterial works."

COURTNEY BAGTAZO, © 2018

BIBLIOGRAPHY

YVES KLEIN, ARTSY.NET

YVES KLEIN LEGACY IS MUCH MORE THAN BLUE, Tess Thackara. ARSTY. Jan 9, 2017

FEMINISM AND YVES KLEIN’S ANTHROPOMETRIES, Kirstin Russell. WALKER ART CENTER, Jan 19, 2011

“Overcoming the problematics of Art -The writings of Yves Klein”, Spring Publications, 2007