FEMALE STUDY: LIUBOV POPOVA'S UTILITARIAN ART

Painterly Archietetonic, 1917

You might have noticed I've been into Russian art this season. This week I looked at the work of yet another Russian artist, Liubov Popova, a founding member, and one of the only female constructivists of the early 20th century. I'm pretty impressed with Popova because of her range of work, and the amount of theory she applied to her work. From line drawings, linoprints, water color and oil paintings, to graphic and textile design, most of which was politically charged, Popova had a prolific though short career as an artist.

Active from 1912-1929, Popova worked in a few styles before helping create the Russian Constructivist movement in the early 1920s. Starting with cubo-futurism, a popular style of the time, Popova employed the use of lines, color and shapes to create her pieces. (I could care less about cubism or cubo-futurism so I'm not posting any of her work from that era. Sorry not sorry).

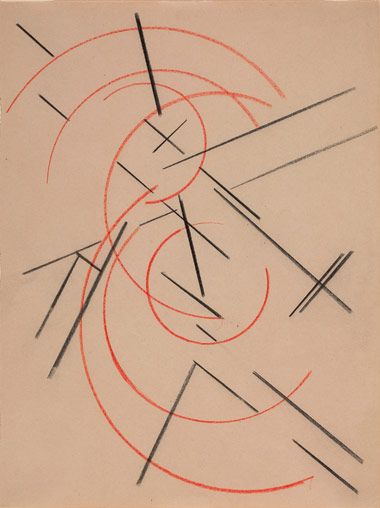

Shortly after the start of her career, Popova employed the Supermatist style that was developing around 1917 in Russia. It is from this point on that Popova really starts to innovate. Unlike most of her male counterparts, she was more willing to work with curved shapes beyond just a circle. She used rounded lines, and even dared to use color as shading, rather than simply creating geometrical shapes with it. (And fine, maybe she adopted that from cubo-futurism).

In 1921, Popova was one of five artists who participated in a show called, 5x5=25 in Moscow, a show that some critics claimed was "the end of art." (She was the only female in the exhibition). Showing minimal paintings with exposed canvas, viewers were left confused and accused Popova of 'fleeing painting.' On the contrary, Popova wrote, "all pieces presented here should be regarded as merely preparations for concrete construction," which was basically one of the first steps towards constructivism in history. In a highly political exhibition, Popova and the other four participating artists rejected expressionist work that was common before WWI. Their goal was to create an entirely new culture where the proletariat was the focus. (This was known as proletkult in Russia).

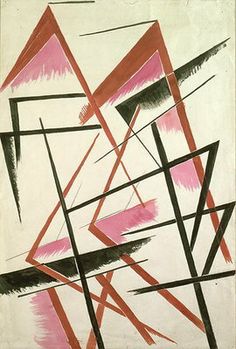

From her work in Supermatism, Popova began exploring the reductivist use of shape, line and color, inadvertently helping create the constructivist movement. Working in Communist Russia, constructivists of the early 20th century rejected what they thought was frivolity in traditional art, instead creating art for social purposes. Constructivists sought to combine faktura, the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence, in attempt to participate in the construction of the then-new Communist spirit, by using artistic skills to design everyday objects for mass production.

So this is where I start to get super into Popova. I've been working in production for over a decade for a few of the same reasons. For me, fashion is the most commercial of my creative endeavors and since I need to make a living, it's where I chose to focus my energy since my early 20s. Plus I'm really into the laborer, which I actually got from the Communists, but more about that another time... And where Liubov Popova and I intersect, is our interest in making things that have a purpose. Yes, most fashion is beyond necessity, but compare a necklace to conceptual architecture, and you can see what I mean about function at least. (Queue the useless wall hanging textiles that are everywhere right now... hello, that's not what rugs are for).

To back herself up, Popova said in an untitled manuscript written in 1921:

The era that humanity has entered is an era of industrial development and therefore the organization of artistic elements must be applied to the design of the material elements of everyday life, i.e. to industry or to so-called production.

The new industrial production, in which artistic creativity must participate, will differ radically from the traditional aesthetic approach to the object, in that primarily attention will be focused not on the artistic decoration of the object (applied art), but on the artistic organization of the object in accordance with the principles of creating the most utilitarian object…

If any of the different types of fine art (i.e., easel painting, drawing, engraving, sculpture, etc.) can still retain some purpose, they will do so only: 1. While they remain as the laboratory phase in our search for essential new forms. 2. Insofar as they serve as supportive projects and schemes for constructions and utilitarian and industrially manufactured objects that have yet to be realized.

Applying this philosophy to her work hereafter, Popova and her colleagues created in effort to support the Bolshevik revolution. During this time, there was civil war going on, and many of the artists in Russia were Communist, so their work reflected their political and theoretical views. Working with architect Aleksandr Vesnin and the avant-garde theatrical director Vsevolod Meierkhold, Popova work on the sets for a ‘theatrical military parade’, which was called ‘The End of Capital’ and was to take place in Moscow that summer to celebrate the meeting of the Congress of the Third Communist International, a communist gathering that was held in 1921. This performance was proposed as a mass theatrical event, employing a cast of thousands of people, but was ended up getting cancelled.

Popova then began working with playwrite, Meierkhold where she designed the set and costumes for his production of The Magnanimous Cuckold, which opened in 1922. The following year she also produced the designs for the play The Earth in Turmoil. Throughout this period, Popova was teaching color theory at the Moscow Vkhutemas as well.

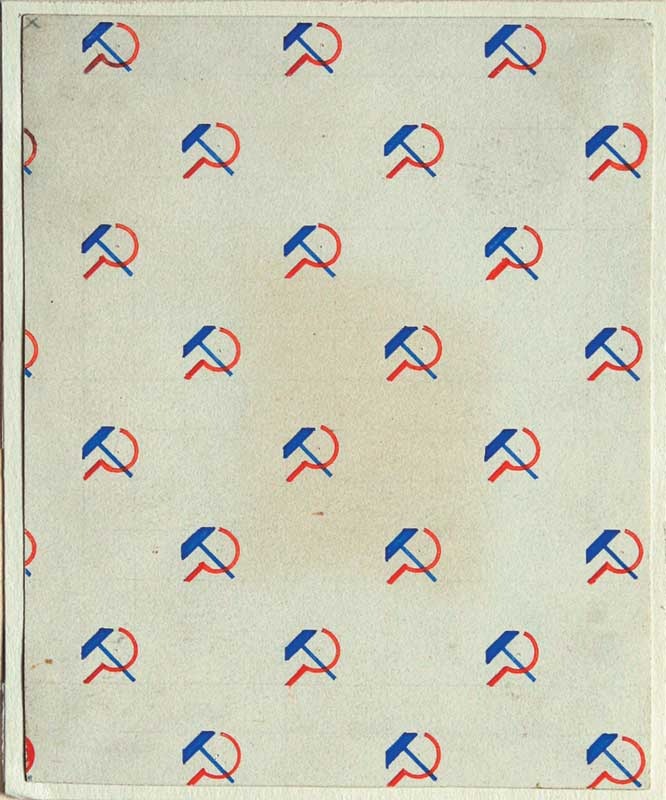

During her tenure at Vkhutemas, Popova was invited to work in the reviving textile industry in Russia as a textile designer at the Tsindel (the First State Textile Factory) outside of Moscow, where she worked with a later female constructivist designer, Varavara Stepanova.

You can see the influence Popova's work in textile design had on Bauhaus, especially among the female artists, as well as the theoretical influence constructivism had on the school in general. I really love Popova's later work in textile design, both from an aesthetic standpoint and a theoretical one. While it's not necessary for art to serve a purpose beyond 'art for art's sake,' I do really appreciate the political drive behind Popova's work. To use one's creativity as a means to reject social norms and question the status quo is never a bad thing (even when it's communist), and honestly these days, having a voice and actually saying something is so difficult to do, especially in fashion where commercial ads disguise themselves as sociopolitical statements, so I kind of envy a time when artists could do this effectively and noticeably.

Anyway, Liubov Popova's career was sadly cut short in 1924 when she died of scarlet fever at the age of 35. I feel like maybe she would have moved to Germany if she had lived longer, or maybe she would have started a Russian equivalence to Bauhaus, given the trajectory of her work, but we'll never know. Either way, considering her career started at the age of 23, and she only worked for thirteen years, her effect on art history is massive. And to be a woman working in the early 1900s with recognition was no easy feat either.

New hero right here vvv

Shout out to:

Christina Lodder, 'Liubov Popova: From Painting to Textile Design', Tate Papers, no.14, Autumn 2010.

I've decided I need to start citing the academic pieces I reference in my blog posts. My apologies for not doing it until now. Blogs are the new frontier...

Courtney Bagtazo, © Bagtazo 2016